History

Census Register for Esher Place 29 September 1939

Who was living in your house 80 years ago?

If you live in one of the 80 properties built in the 1930’s, the population Register taken on the 29th September can tell you exactly who was in your house that evening. These were probably the first owners, who laid out your garden, planted your mature trees and maybe named the house.

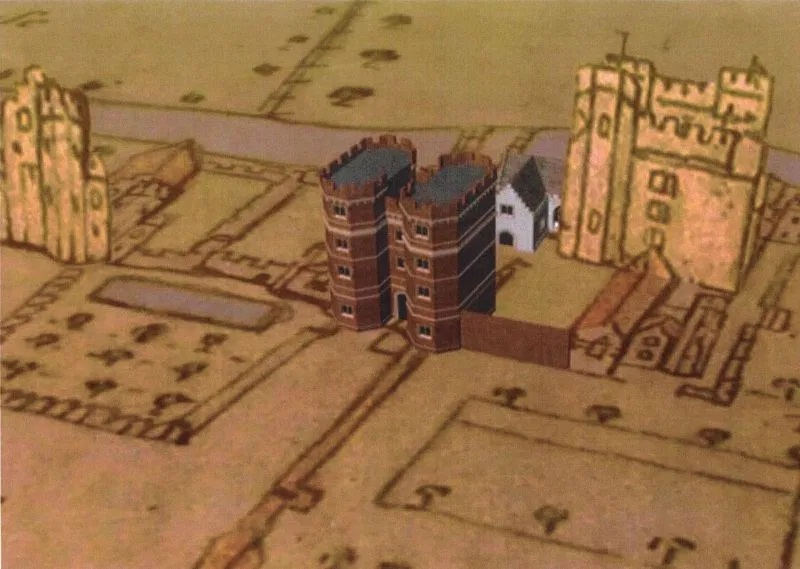

The Esher Place Estate was divided and sold to developers in 1929. Esher Place house itself operated as the Shaftesbury Home for Girls. In 1932, the Estate was advertised as “a hundred yards from the village and most convenient for City men”, 20 properties had been built.

By September 1939, there were 82 properties, of which 10 were unoccupied, including the Tower, on the day of the Register. At the time, the houses had names rather than numbers. The Register data follows the roads sequentially down one side and back on the other. There is no indication as to whether the occupants were owners or tenants.

How different was the estate then compared to now?

The most striking difference is that 42% of the properties had at least one living in domestic servant. The upheavals of the First World War, combined with alternative work such as retail and clerical employment for women, saw a dramatic fall in numbers of residential servants.

However, there was an increase in the domestic servants between the 1921 and 1931 Censuses. In the 1930s, about one third of British women over 15 worked outside the home, of whom nearly a third still worked in domestic service. These were typically single women in the twenties, who left service when they married. However, only one tenth of married women worked.

Recruits were drawn increasingly from abroad, ranging from Jews fleeing Nazi persecution. In 1939, at Latimer, in Winchester Close, Ema Lederer-Davidovics, 32, was one of the 14,000 individuals registered with registered with the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia (BCRC). She worked for the Seward sisters, who were in their sixties, living from “private means”. Next door but one at Trevidren, Amalie Nusabaum, 25, who worked for a retired insurance manager, was probably a German Jewish refugee.

At of Fore Cottage, Wayneflete Tower Avenue, Emilie Steinheim, 24, worked as a housemaid, alongside a cook, for the solicitor William Wakefield and his wife Mable. Very few of the residents had grown up locally. One exception was Lottie Rayment, of The Red House, Esher Place Avenue, and her sister Ellen, who grew in a Lammas Lane and were both married in the local Church.

Age Profile

The average of the owners was 50 for both male and female. Ten of the 72 occupied homes were occupied by retired individuals. One of the few young families occupied Bridgefield, Pelhams Walk where Basil Douglas Napper, 24 lived with his Swiss wife Mabel and their young son. They met when he went to the University of Lausanne to learn French. They were married in 1937 and he was working as an advertising executive at C & F Layton, an engraving business just off Fleet Street. Napper played rugby for Harlequins, which he captained in 1946-7. On the outbreak of war, he was commissioned into the Royal Artillery and served as a battery commander, landing with them in Normandy two weeks after D-Day. He was awarded a Military Cross in June 1944. In 1951, Napper emigrated with his family to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

What was their Occupation?

The predominate occupation was the City with over 10% of the households including stock brokers, a commodity broker, stock jobber, Lloyds Insurance broker and a Bank of England official. Living at Pine Crest, Pelhams Walk was Hargreaves Parkinson, 44 was editor of the Financial Times from 1945 until 1950. He was educated at Blackpool Grammar School and King’s College London. After serving in France during the First World War with the Royal Garrison Artillery he joined the Department of Trade before becoming Assistant Press Officer for the National Savings Committee and then City Editor for The Economist. In 1938, he had become the editor of the Financial News, and it merged with the Financial Times, he moved over to edit the merged paper. Hargreaves Parkinson originated the Lex column in the 1930s. He and his wife Connie are buried at the local Church.

The other occupations listed give an insight into the affluent and aspiring 1930’s middle class. There was the Electricity Commissioner, Chief Economist Central Electricity Board, electrical engineers, the Kingston Borough Surveyor, architects, bank managers, chartered accountants, company secretary, MD of Johnson Matthey, directors of manufacturing businesses and two master tailors.

Apart from the domestic servants, there were relatively few women working or had worked outside the home. Zelma Muriel Blakely, who lived at Bower Bank, Esher Place Avenue studied at Kingston School of Art from 1939 to 1942. She was at Slade School of Art from 1945 for three years. After the Slade, she established herself as a printmaker and book illustrator for which her preferred technique was wood-engraving. She was elected an associate member of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers in 1955. Further along Esher Place Avenue, at Allershaw Lodge, Eliza Dalgleish Ewart, 53, chartered masseur had just published A Guide to Anatomy, which had three reprints.

Social Background

Most of the residents had been born during Queen Victoria’s reign. They would have been more aware of social background. At least a dozen residents had a privileged upbringing. Sir John Slocombe Pearse lived at Kinsmead, Pelhams Walk. Ernest Gayford, of Wayneflete on Esher Place Avenue, had grown up in a household in Lancaster Gate with seven servants. His father was a wine merchant. His wife Gertrude, nee Harding, grew up in a household in Kensington with four servants. Her father was a surveyor. Frank Harold Seeman, stock jobber, lived at Wordsome in The Gardens. His father was also a stock jobber with a cook and housemaid. In 1915, he married Blanche Loughbourgh from a considerable household in Holland Park. Shortly after she died, he married the singer Jessie Whittock. Her father was a boot maker’s “clicker” from Somerset. She performed in the very early days of radio in 1924 and on the London stage at the Kingsway Theatre. She then joined the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company in 1925 and performed until 1931. An example of social mobility was Harold Frank Leslie Dixon living at Lumen, Wayneflete Tower Avenue. His father was a clerk in Lewisham, who was divorced for cruelty and adultery and died in the Workhouse. The son, Harold became a Chief Electrical Engineer, Freemason and moved to Lumen on Wayneflete Tower Avenue. His daughter became the personal secretary to the Conservative politician and journalist Sir Harry Brittain. She married him, as had his previous secretary, and became Lady Brittain.

Many lives had been impacted by the two world wars. Civil engineer Felix Duncan Tunnicliffe had just left his home at 53 Esher Place Avenue for India. He had been awarded the Military Cross for action at Battle of Beersheba 1917 by the Australian Imperial Force. Whilst serving in Bengal, he married Australian Winifred Tulloch and on 16 September 1939, he sailed back to India to work as a government official and returned in 1945.

These individuals and families have left us both a physical architectural legacy and a social inheritance. They established the look and feel of the Estate.

Nicholas Shorthose, May 2019